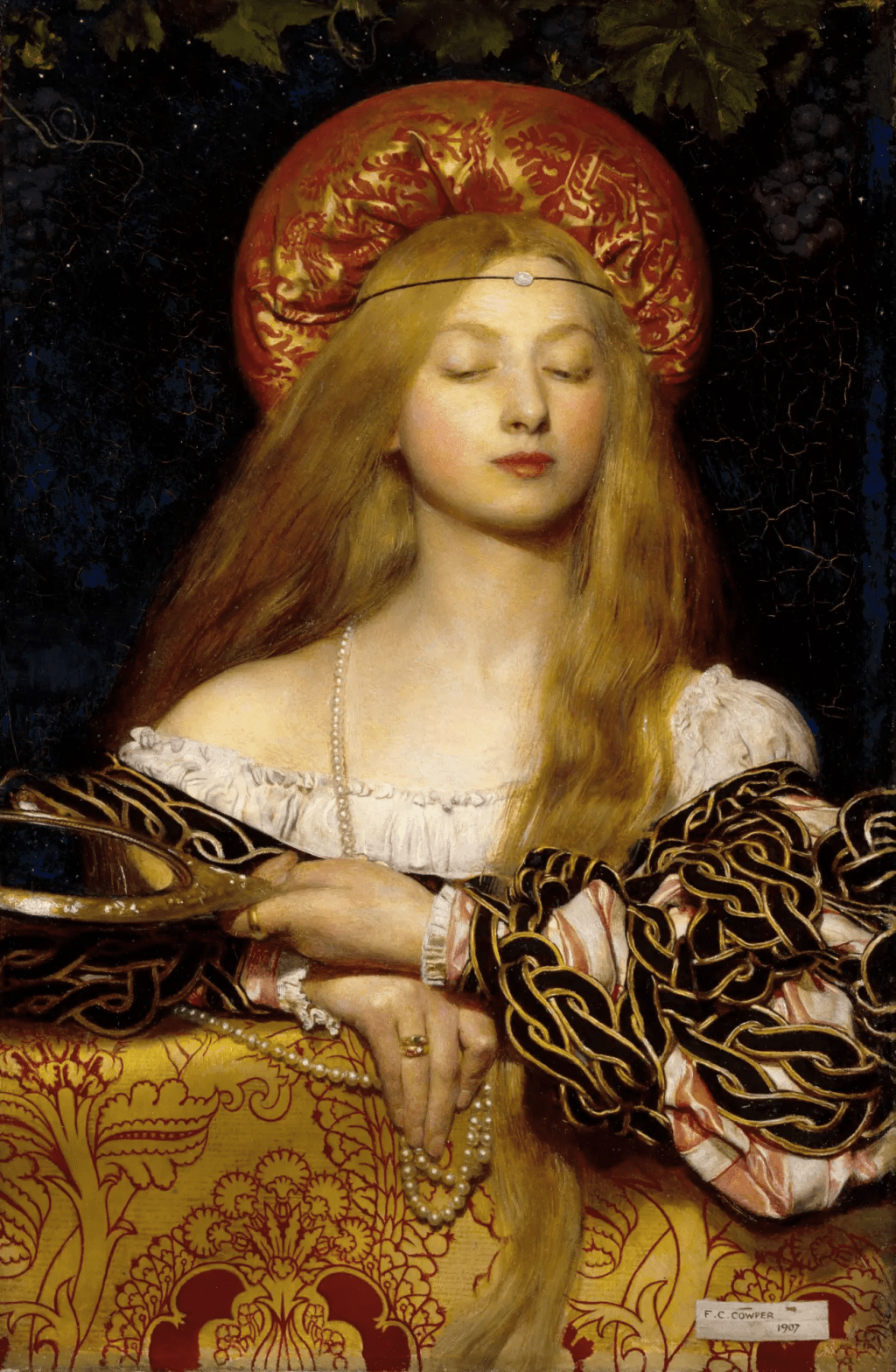

FRANK CADOGAN COWPER, 1907

A young woman in Renaissance dress gazes languidly into a hand mirror, entranced by the sight of her own reflection. Though she may appear to be a simple allegory of self-obsession, the form of Vanity which Frank Cadogan Cowper titled the painting after is not that of conceit, but rather of inconsequentiality.

Taking inspiration from a genre of art called vanitas which rose to popularity in the 16th century, Cowper – like the Renaissance painters before him – warns against the futility of attempting to find fulfilment in material goods and desires, urging the viewer to devote themselves to spiritual, rather than earthly, enrichment. The genre rose from a longstanding artistic tradition of memento mori, a Latin phrase meaning ‘remember you must die,’ which sought to remind the viewer of their own mortality. What sets apart the vanitas genre from other art in the memento mori tradition is its vision of the material world as something inconsequential, communicating a belief that earthly riches, power, and glory mean nothing in death.

With motifs from fruit and flowers to skulls and soap bubbles, works in the vanitas genre typically wove symbols of ephemerality with displays of human wealth and accomplishment to suggest that these too were only fleeting. Cowper incorporates this in Vanity by placing a grapevine behind the young woman, hinting that just as the grapes will inevitably ripen and rot, so too will she age and die.

In art, grapes can signify pleasure and prosperity, so were perhaps simply intended to be counted among the other vanities on show in the painting. However, they are also a common symbol of salvation as they are described in the Bible to represent the sacrificial blood of Christ, meaning that Cowper may have included them here to suggest that if a person is able to rise above vanity, then redemption and eternal reward will await them in the afterlife.

In the case of the young woman pictured, though, her attention is turned away from the fruit and fixed on her own reflection, seeming to indicate that she prioritises superficial matters of appearance over meaningful matters of spirit. It is a characteristically Pre-Raphaelite painting not only in its meticulous attention to detail and vivid colouration, but in the strong moral message it conveys. Cowper has often been lauded as one of the last inheritors of the Pre-Raphaelite tradition, and its influence can be clearly read in Vanity, which channels the spiritual themes and social criticism inherent to the movement.

Under the guise of Renaissance revival, Cowper enlists Vanity as a means of condemning the growing materialism and secularisation he observed in Britain following the Industrial Revolution. It was evidently a painting of great personal significance, and upon being elected to the status of Royal Academician in 1934, he bequeathed Vanity to the Academy as his magnum opus. Since then, the painting has been met with criticism for its message and manner of execution alike, though it is nonetheless a thought-provoking piece which invites all to take pause and ponder how a meaningful way of life looks in our view.

Leave a comment