EL GRECO, 1586

El Greco’s work never fails to catch the eye. Engaging, and alarmingly modern, he immediately stands out from his contemporaries. Once an apprentice to Titian, whose influence still resonates in his striking colours, El Greco created The Burial of the Count of Orgaz for the Santo Tomé church in Toledo, Spain. The real-life Count of Orgaz was an aristocrat and philanthropist who is thought to have donated a great deal of money to the Santo Tomé before his death. However, for over 200 years, town officials ignored his request to donate, preventing the church from accessing the money. This continued on until 1569, when Andres Nuñez, a priest at the Santo Tomé, fought a legal battle to win back the donation for the church. Upon his success the priest used the money to decorate the church in honour of the pious Count of Orgaz, and commissioned the equally pious El Greco to illustrate the famous legend of the Count’s death.

As a deeply religious man, as well as the mayor of the town of Orgaz, Don Gonzalo Ruiz (who later earned the posthumous title of ‘Count of Orgaz’) was a something of a local hero in his day. Though now we remember him for a far different reason, as it is believed that after his death in 1323 a miracle happened. During his funeral, Saint Stephen and Saint Augustine are said to have descended from Heaven to bury the Count themselves – laying him to rest in the grounds of the Santo Tomé church. Some versions of the legend describe the sky opening up to reveal a host of saints and angels, while others claim that the awe-struck mourners witnessed a vision of the Holy family. Regardless, the legend of the burial of the Count of Orgaz remained popular in Toledo in the centuries that followed, eventually being immortalised in El Greco’s monumental painting.

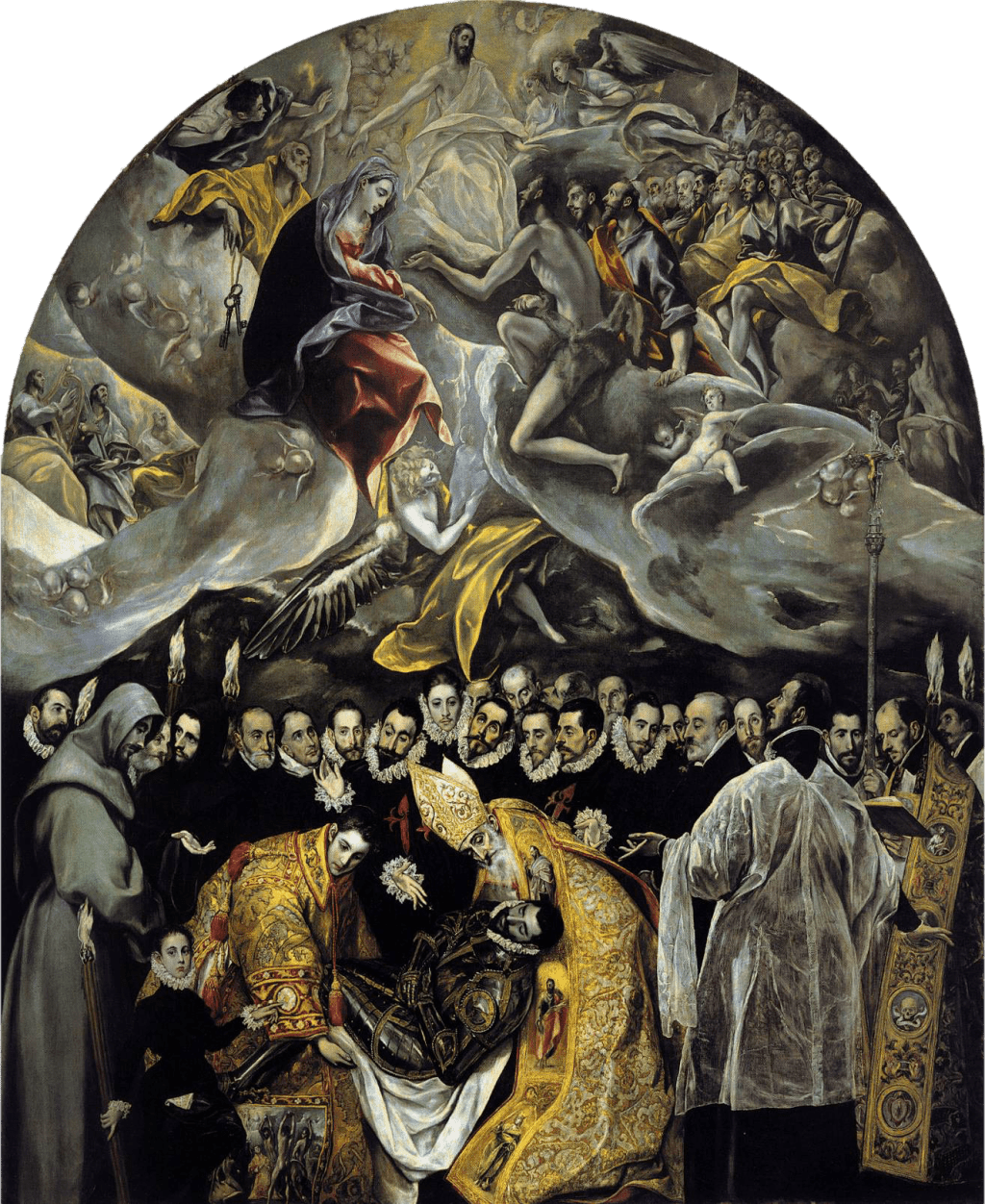

The piece is comprised of two main sections: the realms of the earthly and the heavenly. Up above, the elongated, spectral figures of the saints congregate around the Holy Family who are flanked by a choir of angels, all of which seem to extend up and out of the picture space. The colours here are bright and luminous, and El Greco deliberately exaggerates the scale of his figures to emphasise the vastness of this heavenly realm. The Holy Family sit huge and steadfast in the foreground whilst the tiny figures of the saints stretch off into the distance. Meanwhile, in the earthly realm, everything is much flatter. The mourners are arranged in line with one another, and (bar a few slight height differences) share almost identical proportions, creating a rigid, claustrophobic feel. Likewise, their black robes dominate the lower half of the composition, stark and oppressive as opposed to the airy lightness of heaven. All this is interrupted by the glittering golds of the descended saints, who provide us with the link between the earthly and heavenly realms – their sumptuous robes bringing heavenly splendour to an otherwise sombre scene.

The image clearly stresses the importance of piety, showing us an example of how we may be rewarded for our good deeds in life. To speak to his audience more directly, El Greco has modernised the legend, setting it firmly in the age of the Renaissance. There are several notable modern touches in the painting, for example the Count’s suit of armour which resembles that traditionally worn by Spanish Kings in the 16th century. Similarly, the vestments belonging to the saints and clerics are again based on 16th century counterparts, and even the funeral itself follows the modern rituals of the Renaissance age. In fact, Father Andres Nuñez actively encouraged El Greco to ‘update’ the legend and paint it as if it were taking place in their current day and age, perhaps in an attempt to engage with contemporary viewers.

El Greco’s innovative take on this local legend was celebrated at the time, being lauded both for its artistic prowess and its support of Counter-Reformation beliefs – particularly the idea of saints as intercessors between heaven and earth. Even so, it was primarily his lively figures that drew in crowds soon after the painting was completed. El Greco merged the fantastic and the historical by modelling his mourners after esteemed men of society and of the church, and for years these highly realistic figures have tantalised the public. They are so realistic that we can identify and name individual figures from their ranks, such as the small boy at the front of the image, thought to be the artists’ son. Even El Greco himself can be spotted among the crowd. Consequently, the work is not only a masterpiece of religious painting, but also a masterpiece of portraiture, and The Burial of the Count of Orgaz continues to be praised as one of the great triumphs of art history.

Leave a comment