HENRY FUSELI, 1781

Met with both fear and fascination, Henry Fuseli’s infamous painting “The Nightmare” has become emblematic of Gothic horror, going on to inspire such works of literature as Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” and Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher”.

Standing at approximately 1m by 1.2m, this oil on canvas piece was first exhibited in 1782 at the Royal Academy of London where it became an instant success. Critics were struck by Fuseli’s sinister, haunting expressions of sensuality, some arguing that the piece was needlessly erotic, whilst others interpreted the image as simply intending to shock or scare the viewer.

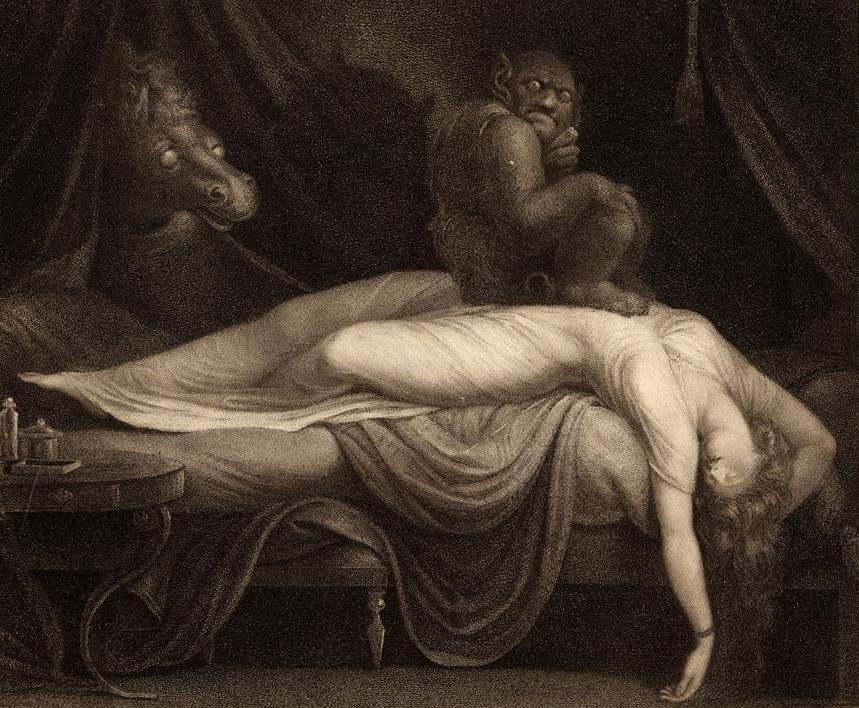

Though the meanings of the piece run deeper than this, “The Nightmare” was arguably one of the earliest paintings to depict an idea, rather than the more traditional subject of a person, landscape or story. Here, Fuseli explores the idea of dreams and the unconscious. The main figure, a young woman, lies on her back with her right arm trailing along the ground, seemingly fast asleep. However, we can easily deduce that the dream she is experiencing is not a pleasant one. Her expression seems pained, and the ghoulish figures leering from the darkness indicate the darker themes at play here.

The word “nightmare” is derived from the Scandinavian “mara”, a mythological spirit said to torment sleepers by sitting atop the person’s chest in the night. Here, the nightmare that the woman endures is embodies by the squat mara crouched upon her torso. The thick, dark brushstrokes contrast with the delicate drapery of the sleeper’s dress, emphasising this idea of weight and compression. The mara both indicating her torment, and evoking the feeling of chest-pressure experienced whilst dreaming.

Furthermore the mara holds the viewer’s gaze, staring indignantly back at them. However, the blank eyes of the ghostly horse seem affixed upon the sleeping woman, its head peeping through the parted red drapes in the background. Though unlike the mara, the horse was a later addition to the image, having been left out of early compositional drawings and only introduced in the final painting. The horse, or ‘mare’ is likely a visual pun on the word “nightmare”, and is often interpreted as an onlooker or intruder into this sexually charged scene.

It has been widely speculated that the painting is a representation of Fuseli’s own experience of lost love. Having fallen for Anna Landholdt while in Zürich, Fuseli wrote extensively of his fantasies toward her, going as far as to claim that “She is mine, and I am hers. And have her I will”. Though his marriage proposal was met with scorn from Landholdt’s father and she married another soon after, leaving Fuseli heartbroken. Thus, “The Nightmare” is often taken to represent his remorse at having lost Landholdt to another.

The back of the canvas showcases an unfinished portrait of a woman, which is thought to be Landholdt herself. Being visually similar, most notably in the striking red curtains in the background, this portrait is often thought to confirm Landholdt’s influence on “The Nightmare”.

This interpretation is further supported by the blatant sexuality of the scene, likely stemming from Fuseli’s desire for Landholdt. Through the sleeper’s provocative position and idealised appearance, Fuseli seems to mourn for the woman he cannot attain. Unable to posses her physically, he instead obtains her through his art, enacting his revenge upon her sleeping figure in this sinister scenario – leading many to interpret that the mara upon the woman’s chest may even represent the artist himself.

Fuseli’s rendition of this scene is incredibly dramatic. The dim light source gives the sleeping woman an angelic glow, yet struggles to permeate the darkness around her, emphasising the adversity and hopelessness she faces here. Long, sloping shadows and deep pits of darkness create a claustrophobic atmosphere, drawing close attention to the figure and the spirits that torment her. Additionally, the bold reds of the curtain and drapes allude to a metaphorical sea of blood, adding to the macabre themes of the image. Potentially giving the viewer an insight into the sort of horrors that the woman dreams of.

This theatricality likely contributed to the success of the piece. After first making an appearance at the Royal Academy of London, “The Nightmare” was described by John Knowles (Fuseli’s biographer) to have excited “an uncommon degree of interest” and remained popular ever since. Cheaper copies of the image were made and distributed, such as Thomas Burke’s engraving which was accompanied in print by a short poem by Erasmus Darwin entitled “Night-Mare”. These more affordable counterparts allowed the image to circulate round the general public, whilst Fuseli’s later versions of the painting can aid our interpretations of the subject.

Despite being created during the Age of Reason, wherein spirits, superstition, and the paranormal were no longer widely believed in, “The Nightmare” captivated and horrified its viewers. In the centuries that followed, the image became infamous for its amalgamation of fear, sexuality, and the supernatural. The reproductions, and subsequent variations of the painting have enabled Fuseli’s work to reach a wide audience, establishing “The Nightmare” as an unforgettable symbol of Gothic horror, that continues to resound with viewers to this day.

Leave a comment