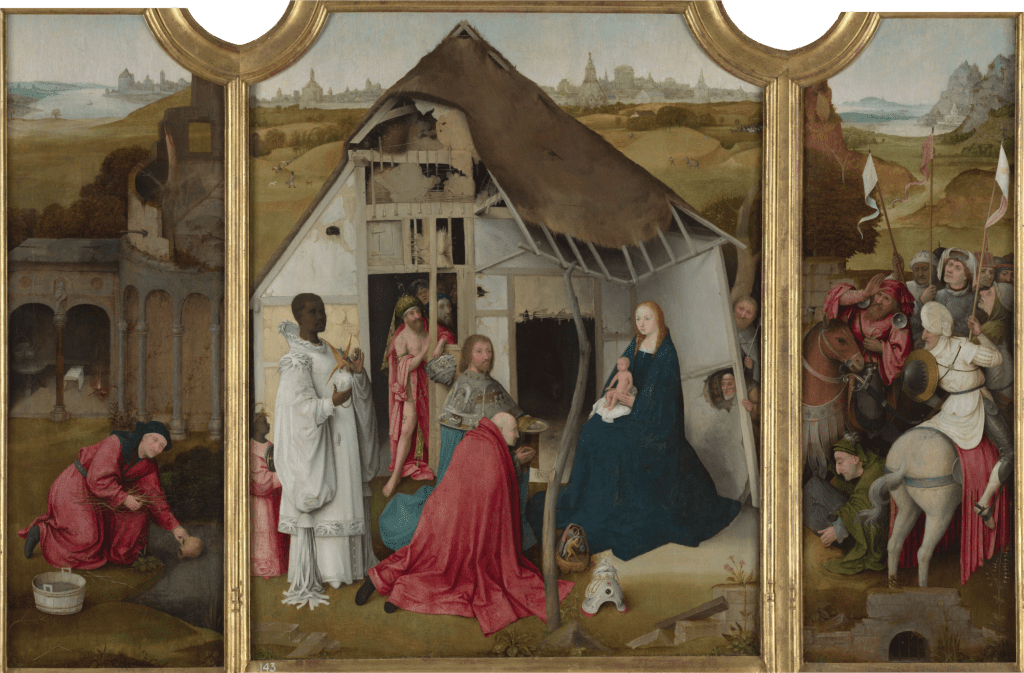

attr. HIERONYMOUS BOSCH, c. 1495-1500

“On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshipped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.”

Matthew 2:11

Bosch’s work is notorious for its complex use of symbolism, and his triptych “The Adoration of the Magi” is no different. The oil on oak panel piece stands at approximately 0.9m by 0.7m, currently a part of the Upton House collection. The piece depicts the biblical scene of the Adoration of the Magi, in which the three Magi (often referred to as the wise men, or the kings) present gifts to the baby Jesus.

Here the three Magi are positioned on the central panel of the triptych, to the left of the scene. The white-robed man holding the orb and phoenix has been identified as Balthasar, the Moorish King. His orb depicts the Three Heroes offering water to David. This draws a parallel with the scene of the Adoration here, the Three Heroes much like the three Magi offering gifts to the Christ Child. As the most elderly of the Magi, the kneeling, red-robed figure is most likely Melchior, the King of Persia, his unidentified offering placed at the feet of Mary. Melchior’s offering differs from the norm in this version of the triptych, most frequently seen as a golden statuette in Bosch’s other depictions of the Adoration – the reason for this change is still unknown. This leaves the final Magi as Caspar, reaffirmed by his characteristic reddish beard and appearance of being between the other two Magi in age.

Mary, seated in blue with the Christ Child on her lap, is separated from the other figures in the composition. The curved wooden support divides her from the group and she is framed by the beams of the barn – perhaps a physical assertion of her purity and holiness through her untouchable, unreachable appearance. On the left wing, Joseph can be seen gathering sticks and water in preparation for the Christ Child’s bath. On the right wing the Magi’s entourage, mounted on horseback, gaze up at the sky where the star would be seen.

Though perhaps the most puzzling figure is the man looming out from the darkness of the barn, nude, draped with a reddish-pink robe and golden jewellery. This figure has been the subject of much speculation: argued to be the Antichrist, Pilate, or even King Herod. To shed some light on who this mysterious character may be, we can turn to other works by Bosch to better understand his use of imagery.

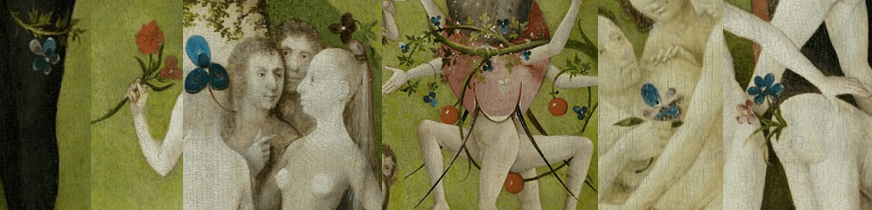

The figure wears a turban of thorns, sprouting a single blue flower – a train draped atop it adorned with pink and blue flowers. These flowers resemble those included in another of Bosch’s triptychs, “The Garden of Earthly Delights”, assumed to have been created during the same period. Evoking themes of temptation, luxury, and frivolity, the inclusion of these flowers may give us some insight into the character of this figure, potentially enabling us to identify him.

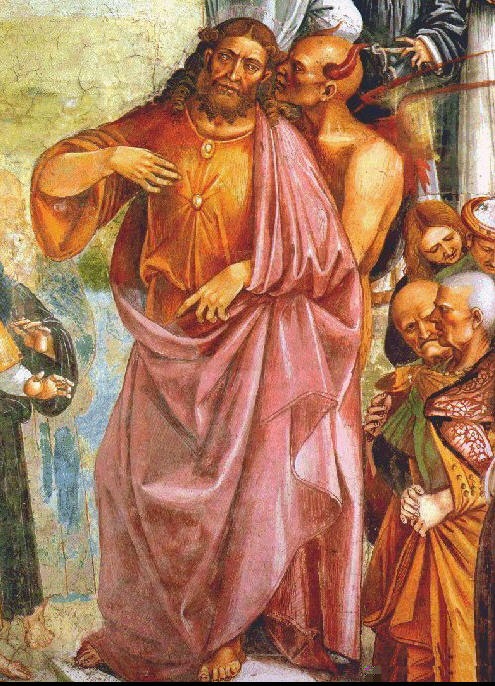

Though, the turban of thorns itself suggests the figure is most likely a rendition of the Antichrist, a play on the crown of thorns worn by Christ at the Crucifixion. This interpretation is somewhat enriched by Signorelli’s “Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist” created around the same time (circa 1499-1502), the figure in Bosch’s piece appearing visually similar to Signorelli’s depiction of the Antichrist.

While this does not confirm the identity of the mysterious figure, it does offer a potential explanation to the meanings they embody. Conforming to the typical image of the Antichrist, as well as being associated with temptation and transgressions through the symbol of flowers, they are undoubtedly an expression of sin. Regardless of their actual identity, this figure presents the choice the viewer must make between good and evil; the former symbolised through the innocent Christ Child, and the latter by the menacing figure of the unidentified man. The two choices physically set apart by the supporting tree branch painted vertically between them.

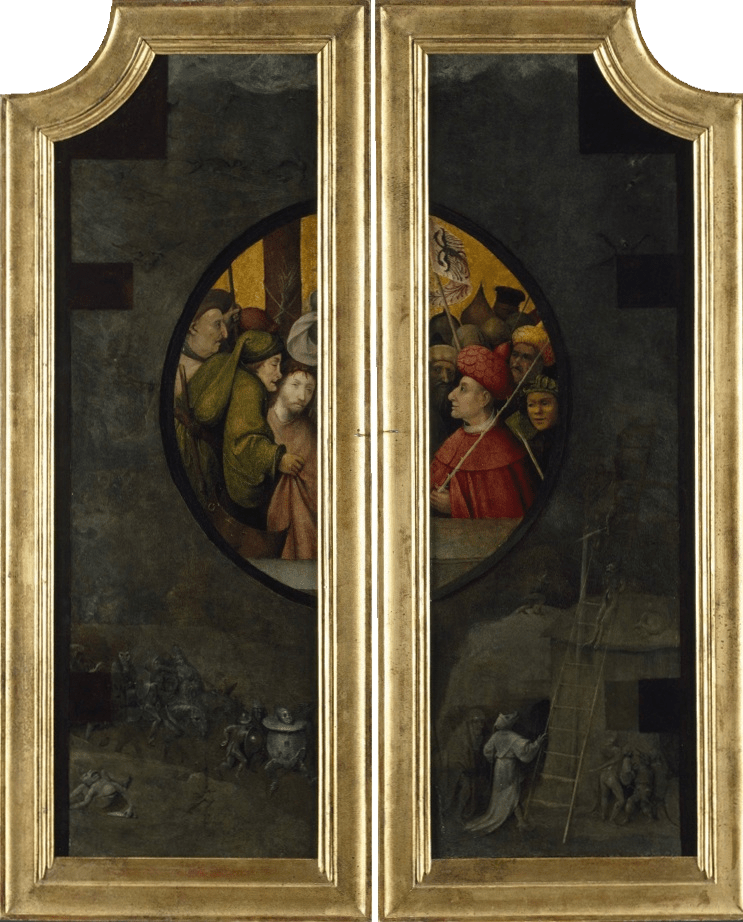

Looking further into Bosch’s depiction of sin here, it is worth considering the image painted on the exterior of the wings.

Once closed, the wings display an image of Christ before Pilate after the Flagellation, surrounded by a gloomy landscape of demons and peculiar hybrid creatures. The bright colours of the roundel enable it to shine out from the darker, muted tones dominating the rest of the scene.

This approach is fairly uncommon for triptychs, especially during the period that Bosch was working in, with most wings deliberately painted entirely in muted tones or grisaille juxtapose the colourful interior. However here, colour intensifies the contrast between the worldly events of Christ’s life and the bleak depiction of hell. Similarly, the divide between Christ and Pilate created by the frame separating them may be a physical representation of their conflicting moral standings, mirroring the separation between the figures of the Christ Child and the unidentified man in the piece’s interior.

Furthermore, the figure of the adult Christ on the wings of the triptych is placed in almost exactly the same position on the panel as the unidentified man on the piece’s interior. This placement could indicate an intentional parallel between the two, aligning the man’s identity closer with that of Christ. Somewhat consolidating his potential identification as the Antichrist. This pair of figures presenting yet another set of opposites within the piece.

While the murkiness of the background conceals many of the events playing out, this darker scene can be read as a summary of sorts, indicating the deeper meanings of the piece.

In the lower right of the scene stands a gallows, surrounded by a gaggle of strange creatures. A sinister being cloaked in white stands out from the darkness of the doorway, appearing to hold on to a ladder. Perhaps a depiction of death or a demon, this figure is unnerving to say the least.

Looking at both its position and mannerisms, the creature has a noticeable similarity to the horseback rider in the piece’s interior, located on the reverse of the wing that this figure is painted on. Both face away from the viewer, the horseback rider looking toward the Christ Child, and the creature looking up at the body on the gallows. From the pale robes and head coverings, to the near-identical movement of the left arm, these figures appear to be connected to one another through their similar compositional elements. While the reason behind this connection is still uncertain, its presence unifies these juxtaposing scenes – emphasising the importance of analysing these two images alongside one another.

This opens up the triptych to a variety of interpretations. When read together, a particular idea stands out in both of these pieces: the corruption of sin.

Both present the importance of faith in Christ through their menacing portrayal of sin and temptation. The looming terror of the Antichrist’s stare, and the hellish horror of the landscape on the triptych’s wings would have reminded 16th century viewers of the importance of devotion; piety encouraged through the focus on the consequence of sinfulness.

Compared to its variant at the Museo Nacional del Prado, this triptych has a much stronger focus on the misery and suffering caused by sin. The alternate version still handles the concept of sin, though chooses to approach it through the lens of human fickleness – highlighting how easily people succumb to foolishness, temptation, and harm.

Additionally, the colour palette of the triptych at Upton is visibly less saturated and vibrant than the Prado version, the scene appearing much bleaker as a result. This creates a gloomier image, struck through by the bright red tones of robes and drapery. Red can often be interpreted to allude to sin (both original sin, and the sins of mankind), and is frequently taken as a symbol of greediness, lust, and temptation. While reading into colour symbolism can quickly become speculative, these strong connotations still enrich our understanding of the piece and its moralising purpose.

At its core, Bosch’s “The Adoration of the Magi” is reliant on contrast to emphasise the polarity of faith and sin. Since the wings of the triptych would most often be closed, the demonic entities populating this hellscape would have been a constant reminder to 16th century churchgoers of the suffering and chaos of hell. The piece works as a warning of sorts to remind the faithful of the importance of refraining from sin and temptation, informing them of the posthumous punishment they would receive for committing such acts. Not uncommon for the work of Bosch, this piece constantly amplifies the horror of sin – ultimately intimidating the viewer into devoutness through its grotesque imagery.

Leave a comment